Here is where I post short articles that I’ve written for parents, teachers, or just any adults who are just interested in the going ons of education and child-care. I try to keep each article below 1,100 words. The world of public schools are filled with a lot of empty buzzwords and it’s easy for someone not in the field to get lost in all the jargon. With these articles, I try my best to clear things up. If you don’t want to read the articles, you can listen to them from my youtube channel.

Language Learning: School vs. Reality (9/27/24)

November of 2023 would mark a major checkpoint in my life as a teacher, a learner, and a human being. I picked up a part time job at my local supermarket. I chose this market specifically for 2 reasons:

1) For the past 8 years of my life I’ve worked in nothing but child-care and education. I wanted to be out of my comfort zone.

2) This market was, and still is, a bedrock in my hometown community. Imagine as if the first whole foods stayed what it was and never expanded past that original location.

I was first hired to work in produce and during my first full 8 hour shift, I heard nothing but Spanish from my coworkers. Yes, they could talk to me in English if they needed to, but for everything else, it was just their native tongues. When I got home that afternoon, my head was buzzing with the cadence and rhythm of their language. I loved every bit of it.

Up until this point in my life I had made 2 genuine efforts to learn Spanish during my twenties. Both times I used nothing but Duolingo. I was obsessed like every other user, and I managed to even maintain a high streak count. I remember having detailed notes with conjugation tables and grammar rules. But despite all that meticulous studying, my brain never felt as close to how it felt that day when I came home from the market. I thought to myself, I want to learn this language now —there’s got to be more to learning a language than grammar exercises and memorization. Low and behold, almost a year and half later, I can confirm that that is just so the case.

The problem with my previous attempts to learn Spanish wasn’t an issue of motivation, it was an issue of approach. It didn’t matter how many hours I spent studying words and grammar rules. It didn’t matter how many correct answers I could give to the green owl. I was studying and assessing my progress with the language in such a computerized way, much like what we have in many public schools today: write down this information, make sure to memorize this information, and be able to answer questions about that information when asked.

This is not how language mastery is acquired. In fact, mastery is not possible. Of course it should be targeted, but one’s journey to learning and understanding the intricacies of their own language never ends. I am at a point now where I can comfortably read children’s literature and adult non-fiction in Spanish, I can watch TV shows and understand what’s going on, and, I can also journal with the help of a dictionary by my side. The teacher in me however, frequently looks back at my journey of language learning. There are clear points where if I were to grade my skills on a certain day, I would have definitely earned failing marks.

Now I see just how backwards and silly that type of thinking is. It never mattered to me to be able to get this amount of questions correct out of 10, or to be able to reach this reading level by this date. No.

I studied every single day of that 1st year, by focusing on engagement with the language. Did I have days where I spent my time studying flash cards or reviewing grammar? Yes I did. But, I also had days where I watched cartoons in Spanish. On some days I read books, and on others I listened to podcasts. In fact, there were days where I read more books than listened to podcasts. The point was just to just keep in contact with the language in ways that were interesting and challenging, but not overly difficult. The variety in study methods helped ease the tedious portions of the learning process.

This knowledge has helped shape my curriculum tremendously. In my last Education Translation, I talked about our reading deficiency problems. Kids are not motivated to read when it’s pushed on them like a boring scavenger hunt exercise. Kids are afraid to write because they’re petrified of making mistakes. As teachers, we are trained to only look for what’s being asked. And what’s being asked, in this case, are matters that real readers and writers consider boring.

- Be able to write the main idea of this article and write the 3 facts you’ve learned.

- Tell me what happened to this character in chapter 2.

- Look at paragraph 5, and explain why you think the author chose do say…

The main goal of teaching reading and writing in this way is to collect good data, not to instill life long habits. Language is a daily exercise. Even if you don’t read, you’re bound to write, and if you’re trying hard enough to not do either, it is almost inevitable that you will still have to speak. By default, our existence hangs on our ability to use language proficiently.

Yes, it is important to adhere to the rules of grammar as best you can. And yes, it is important to be able to understand and analyze the plot points within a given story. But those facts do not warrant obsessing over the measurement of those skills. By obsessing over word count numbers, reading levels, and running records, etc. teachers have taken the organic and spontaneous process of language learning, and turned it into something that is vapid and automated.

I believe the better approach, when it comes to language learning, is to encourage play with the language. Instead of teaching these skills like an obstacle course, teach it like it’s a playground. The grammar rules are the play structure—encourage children to try and explore it in various ways. However, just like outdoor play, there are risks involved. Let children know that when it comes to language learning, they can and will make mistakes, even if they’re following all the rules. They need to embrace that possibility of embarrassment from miscommunication, in order to develop a resolve to better express themselves next time.

Our Reading Deficiency (4/8/24)

Contrary to popular belief, reading proficiency in America has been a point of concern even before the pandemic. Since it’s testing season once again in schools, it only feels right that we talk about the scores we’ve been earning as nation.

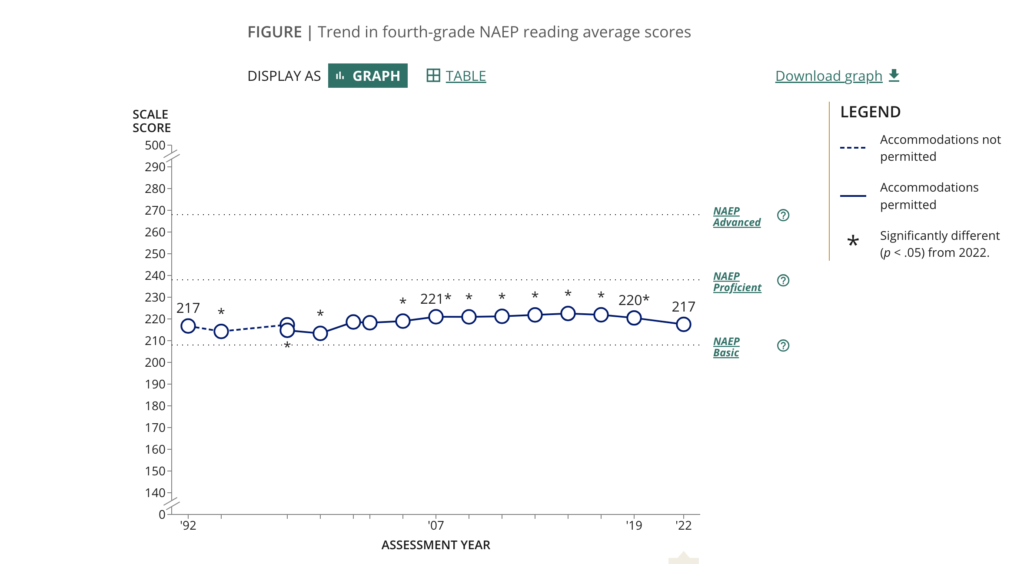

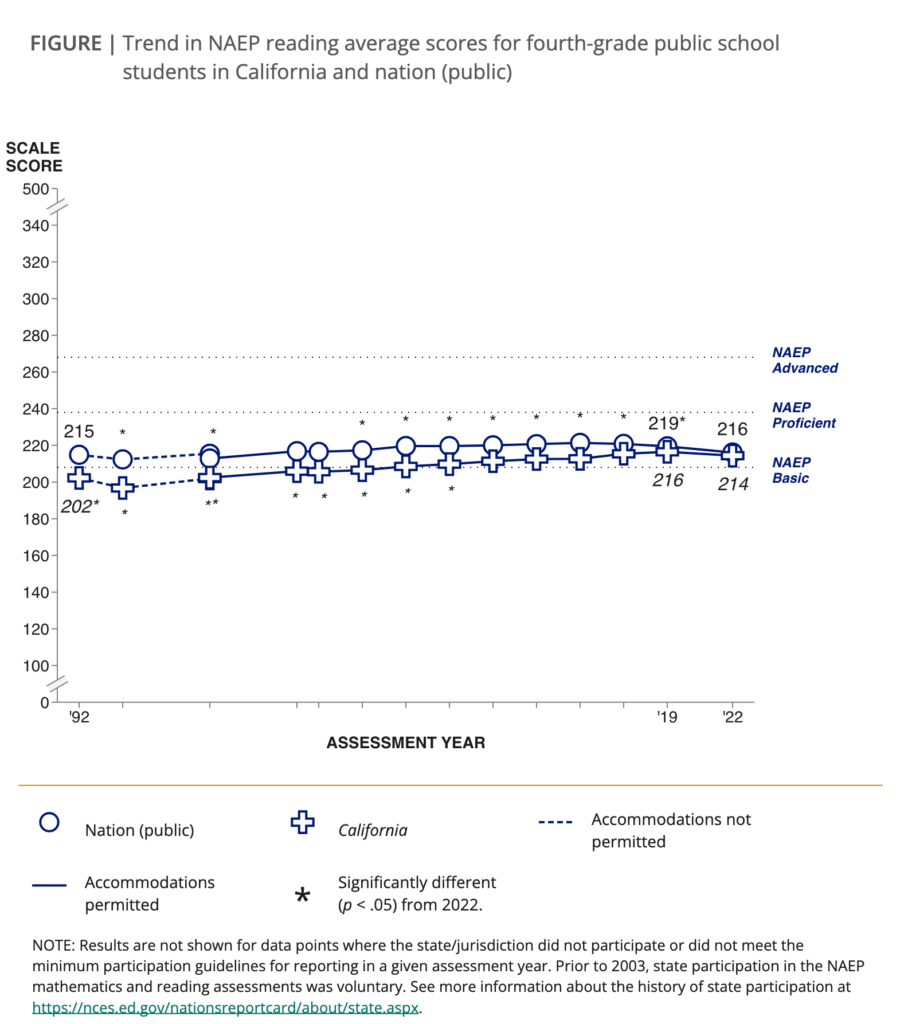

The graphs I will place below are from the NAEP results, for state by state as well as California itself. For those that do not know what the NAEP is, according to their website:

“The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) is a congressionally mandated project administered by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) within the U.S. Department of Education and is the largest continuing and nationally representative assessment of what our nation’s students know and can do in select subjects. The NAEP reading assessment uses literary and informational texts to measure students’ reading comprehension skills. Students read grade-appropriate passages and answer questions based on what they have read.”

As you can see, going state by state, as far back as 1992, not a single one of them has shown an increase in score. In fact, the majority of the states have shown a decrease in their average scores. If you want to look deeper into the graphs, you can do so here. If you click on just the state of California, you’ll see that we’ve been staying consistently below NAEP proficient since 1992. Not once have we been above that line.

The information above is concerning for many reasons and raises many more questions. The most important of which is this: How is it that we’ve gone through so many decades (as a state and a country) without ever achieving proficiency?

I believe the main cause of this problem is the lack of spirit that schools have towards reading and writing. I know that the term spirit isn’t a measurable thing, but from the inside as both a student and a teacher, it’s apparent that schools have never been good at marketing reading.

When I was a kid, I got A’s and B’s all through my English language arts classes. But if any adult told me to read in my free time, I would be dumbfounded as to why on earth would they would suggest such a random idea. My reasoning was like most students today, “I already have to pick up books in school, why would I want to do it now?”

I can understand why kids may think that way and why some parents are struggling to encourage healthy reading habits with them at home. Schools have achieved mediocre results because they teach reading in such a disconnected way. Or, they teach it in a way that is only motivated by results and not the process. In fact, when they do attempt to teach the process of reading, they discuss reading in such a mechanical fashion. Most assessment questions for reading are posed like this:

“Reading Levels..”

“Find the main idea…”

“List 3 reasons…”

“Recall what happened in paragraph 2…”

This approach to teaching reading is misguided. It teaches reading as if it’s just a scavenger hunt for information. In other words, find what’s asked of you, and bring it back. It’s not important to look for anything else.

True reading—reading for curiosity, adventure, or pleasure—isn’t anything like that. Sure we glean information through the process of reading, but reading is such a personal human experience. You and I may read the same novel, but your takeaways from the book could be uniquely different from mine due to our individual lived experiences. To go further, what if there is an event in the middle of the novel that sticks out to you, and for some reason I don’t even remember it. Have I failed in my reading of this book? Are my skills as a reader diminished? This same example can apply to non-fiction books as well.

Perhaps the best argument for this disconnected approach to reading is: “They’re going to need these skills for testing and assessments later on in high school and college.” I believe that is true, they will need it. I’m not arguing against how they’re assessed, I’m arguing over how reading is taught before the assessment. A lot of teachers—all wonderful and kind people I’m sure—rely on teaching ELA through standard curriculum books or applications. They teach to the test, instead of just teaching students to enjoy reading.

Additionally, a lot of teachers teach reading as if they themselves are bored by it. During my time working for public schools, it was alarming to me how little teachers would voluntarily read. Sure, they read memos, emails, books in class to their kids, but when it came to reading at home or even at work, I never saw it. I’m not demanding that all teachers should be reading Crime and Punishment in their free time, but how can you expect the kids to care about reading when you yourself don’t seem to care about it, outside of getting kids to reach a certain number on a test. It’s like being a P.E teacher who doesn’t like exercising.

The solution to this isn’t simple, but I think subtle changes can make a world of difference. I believe all the adults in a child’s life should walk the walk when it comes to reading. Teachers, instead of working on emails when the class is working on assignments, quietly read a book somewhere around the kids. Read books that spark your own curiosity outside of school. Just because school’s over, does not mean the learning stops.

This sentiment needs to be reinforced by parents doing the same thing with their children at home. I’m not asking parents to read in front of their child for hours. Just like teachers, a little a day goes a long way. Quietly read for 10-20 minutes around your kids. Don’t underestimate the power of reading aloud to them as well. Audio books are fine, but if you have an opportunity to read to your child, with enthusiasm and purpose, do it yourself! It’s incredible for a child’s vocabulary growth because it allows them to focus on the context, cadence, and structure of a story. In layman’s terms, you’re exposing them to a ton of words at a pace they might not be able to read at by themselves.